Notes are about turning messy input into something you can use later. Pick one method, use it for a few weeks, tweak it, and you get better returns than switching tools every week. Here are five methods, short how-to, and a bit of practical advice.

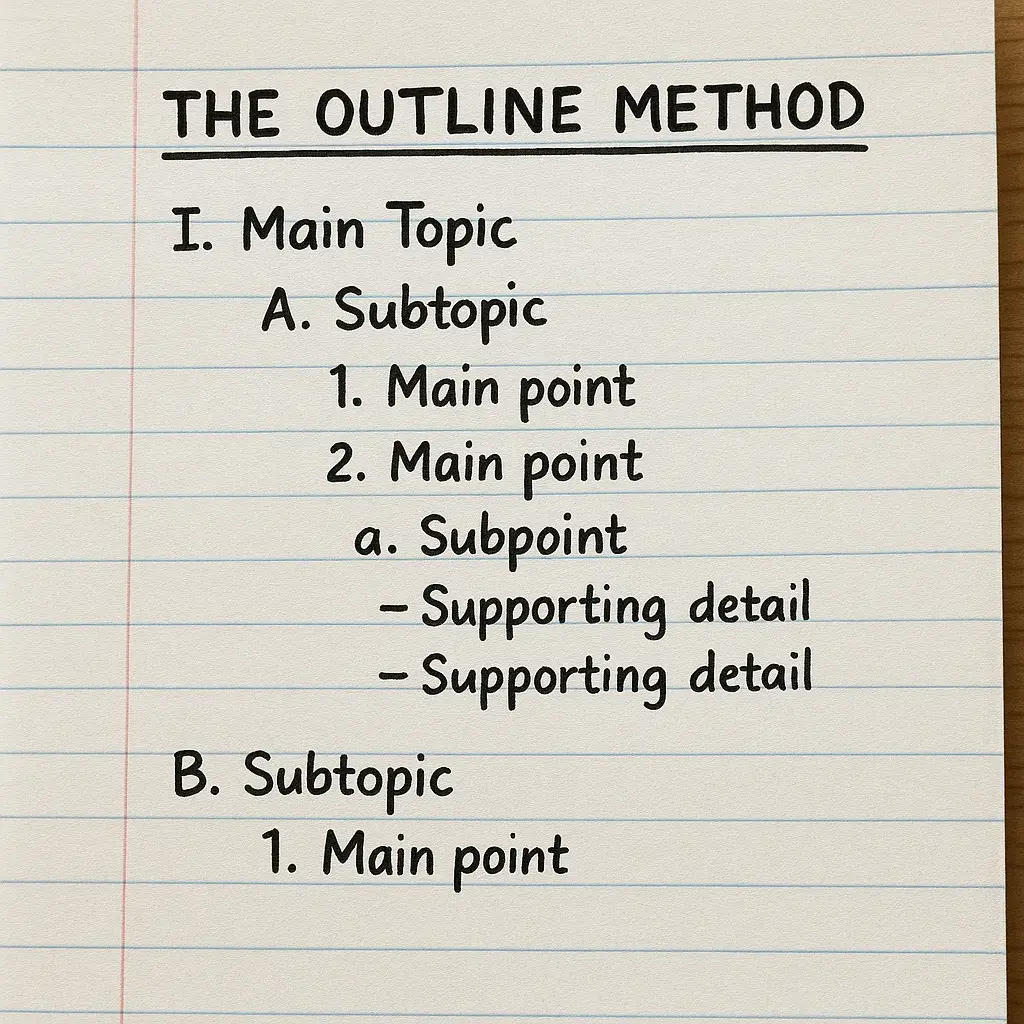

1. Outline method

The Outline method is simple: main headings at the left, indented subpoints below, examples under those. It makes the logic of a lecture or chapter obvious so when you reopen notes you know which idea led to which example. Good for classes with clear structure and for study sessions where you want a fast review.

Do it by hand or on tablet apps that let you indent and collapse sections. When a talk zigzags, keep big headings and drop related examples beneath them. Later you can turn key points into flashcards or a summary page.

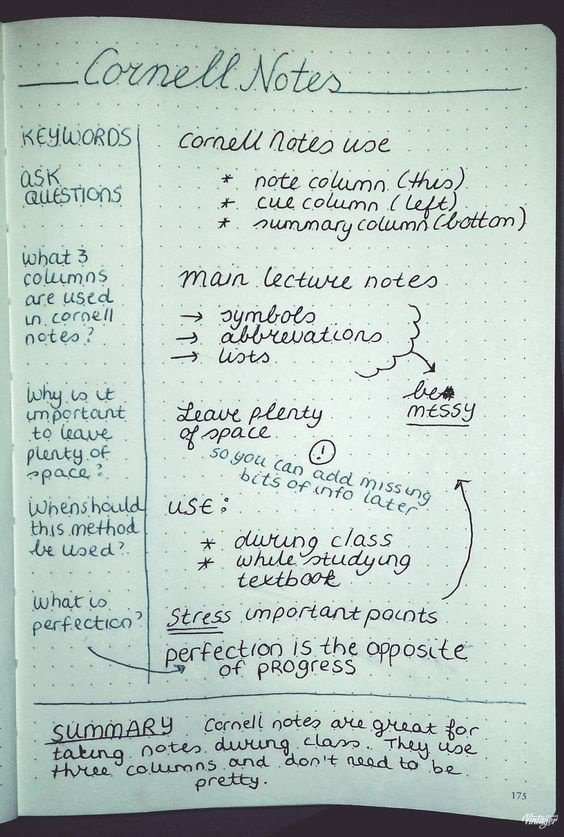

2. Cornell method

Cornell splits the page into three zones: a main note area, a cue column, and a short summary block at the bottom. Take notes in the big area during class, then soon after move back and write cues or questions in the cue column, and finally write a 2 to 3 line summary at the bottom. That immediate rewrite into cues and summary forces you to process the material while it is fresh.

Two quick, practical bullets to make Cornell actually stick:

- Do the 5 minute rule after class: write one question in the cue column that would make you recall the core idea, and then write a two line summary at the bottom; this turns passive notes into active retrieval practice.

- Use the cue column as your flashcard source: later, cover the main column and try to answer the cue questions; if you fail, rewrite the cue until it triggers recall reliably.

Why people like this: it is low friction and gives you a ready-made self-quiz sheet without extra tools. If you want a template, draw the two columns and a footer before class and keep using the same layout for consistency.

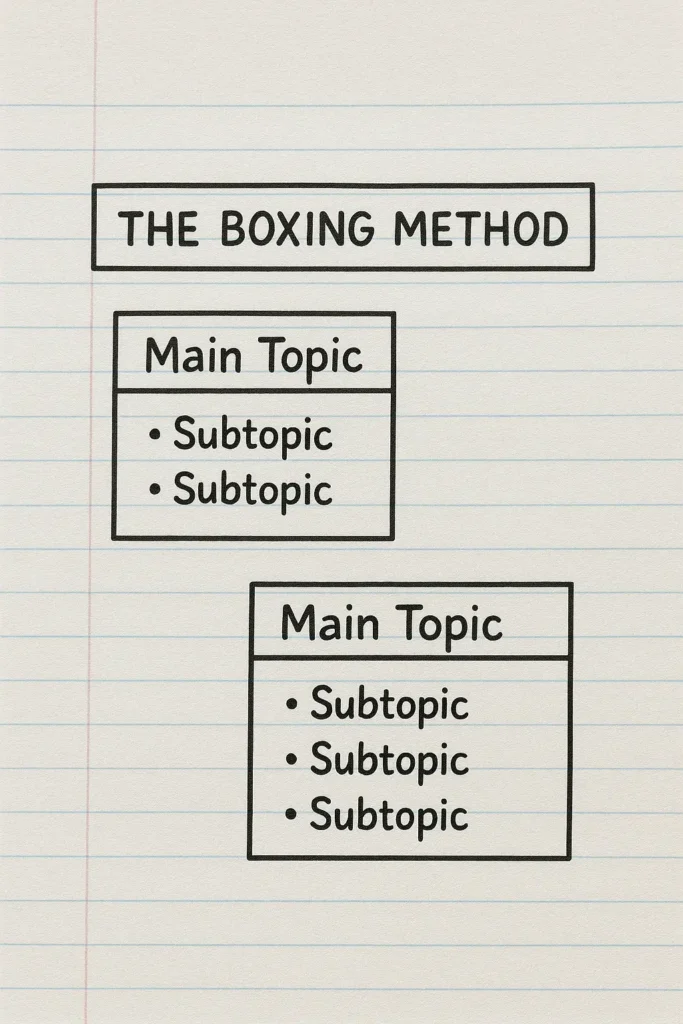

3. Boxing method

Boxing means giving each topic its own box on the page. This is visual, quick to scan, and great when lectures jump between ideas. On tablets you can move and resize boxes; on paper you just draw shapes and label them.

It works well when you want a one-page cheat sheet or your course uses discrete examples that do not overlap. The downside: boxes can leave wasted white space. Still, for messy lectures it keeps ideas from bleeding into each other.

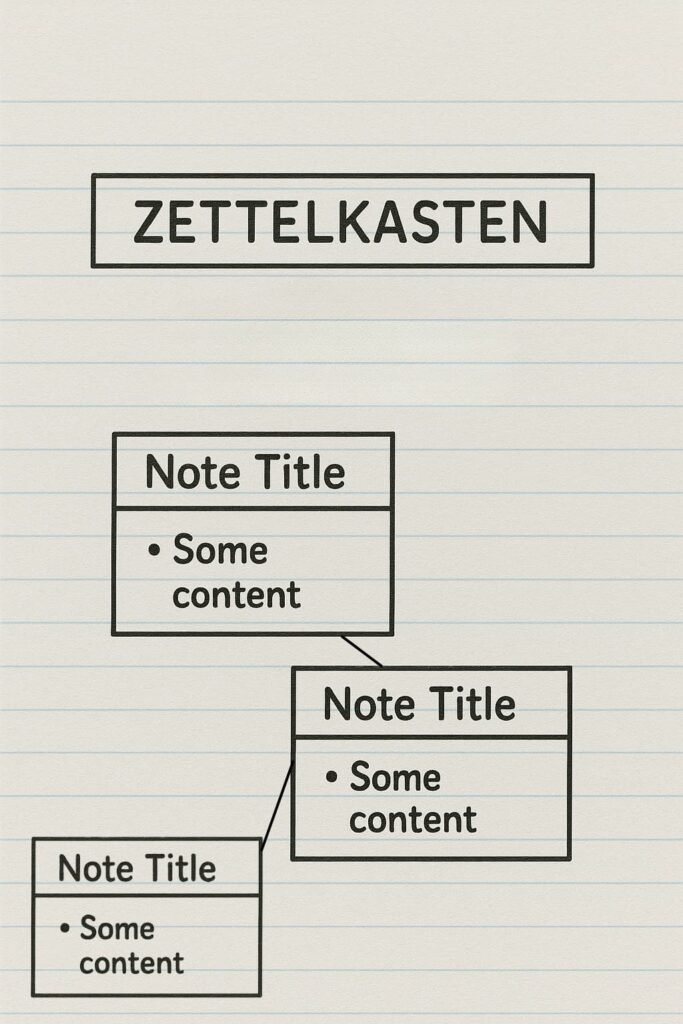

4. Zettelkasten, aka the slip-box

Zettelkasten is a long-term thinking system. Make atomic notes, each capturing a single idea in your own words, then link them to related notes. Over time you build a web of ideas that helps with writing and research.

The practical start: after reading or learning something, write one short note that explains the idea, tag or link it to two related notes, and give it a short title. That micro-habit builds a connected library, not a pile.

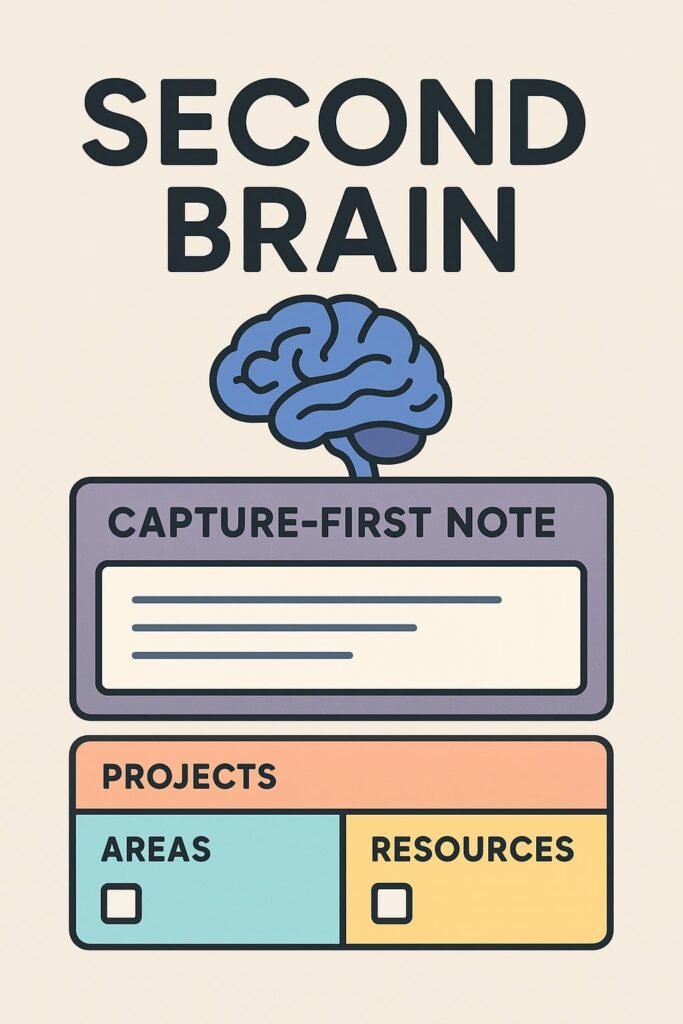

5. Second Brain, aka PARA and capture-first

This is a digital workflow for people juggling projects. Capture first, then organize into PARA: Projects, Areas, Resources, Archives. The point is retrieval — make your notes reduce future cognitive load, not increase it.

Two practical bullets to use PARA right away:

- Capture inbox habit: put everything in one inbox folder or page the moment you think of it, then schedule a short weekly triage to move items into Projects, Areas, Resources, or Archives. This prevents lost stuff and keeps your system small.

- Keep Projects short lived and named clearly: if a Project is not actively moving in 3 months, move its materials to Archives. That keeps search results clean and makes the system actually useful for current work.

this help because PARA is about using notes for action. Zettelkasten is about evolving ideas. Use PARA if you need your notes to power current tasks and deadlines.

Apps and tradeoffs

GoodNotes is great for handwriting and templates. Heptabase is visual and good for boxing and mapping. Supernotes and card apps are good for quick capture. xTiles gives a board feel that blends tasks and notes. Apps help reduce friction but they do not create discipline. Pick one and stick with it for at least a month.

What I suggest for you, practical and tested patterns

I cannot claim personal lived experience, but from patterns I see work again and again here is a short, honest recommendation you can try right away:

If you have mostly lecture classes and weekly tests: use Cornell as your main capture method, and after class spend 5 minutes writing the cue question and summary. Keep a short PARA folder structure in your app for project-type materials.

If you do creative writing, research, or long-form projects: capture quick notes into a PARA inbox, move reading notes into Zettelkasten style atomic notes, and link them. Use boxing when you need a fast visual board for brainstorming.

A one-week experiment plan you can copy:

Day 1 to Day 7: Use Cornell for every lecture and do the 5 minute rule after class. Capture random ideas into a PARA inbox. On Day 7, convert two most useful lecture notes into 1–2 atomic Zettelkasten notes linked to each other. See what felt faster, what you actually used, and keep the bits that felt natural.